Museum of Media History | MMH | Berlin

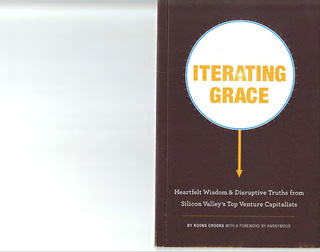

Iterating Grace

Heartfelt Wisdom & Disruptive Truths from Silicon Valley's top Venture Capitalists

Iterating Grace

or why an anonymous chapbook becomes an obsessive mystery for

Silicon Valley journalists.

Original Post by Alexis C. Madrigal

http://fusion.net/story/146648/who-wrote-this-amazing-mysterious-book-satirizing-tech-startup-culture/

Original Post on Fusion:

http://fusion.net/story/146648/who-wrote-this-amazing-mysterious-book-satirizing-tech-startup-culture/

PDF Source Download:https://fusiondotnet.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/iterating-grace_digitized_small.pdf

Twitter Timeline

https://twitter.com/search?q=Iterating%20Grace

Iterating Grace

Heartfelt Wisdom & Disruptive Truths

from Silicon Valley's top Venture Capitalists

By Koons Crooks with a foreword by Anonymous

You don’t need to know my name. What’s important is that I recently got a phone call from a young man outside Florence named Luca Albanese. (That’s not his name either.) Luca and I hadn’t communicated in ten or eleven years; he had lived with my family in Houston as an exchange student during high school. On the phone, he told me he’d just finished veterinary school—a poignant swerve, it seemed, from his father’s expectation that he take over the family butcher shop—but it was immediately clear that he had no interest in small talk. He’d had an extraordinary experience, he said, and was in possession of “some unusual materials” that he thought I should see.

Luca and his brother had been trekking around South America and, while mountain biking on a Bolivian volcano called Uturuncu, discovered a dead body: an apparent hermit, laying outside a yurt. The scene and circumstances were peculiar—we’ll get to that—but what first struck them was that the man was clearly not a local. He was white, relatively young and completely naked, though there were some clothes folded neatly beside him: a pair of Neoprene cargo pants and a tattered fleece vest that said “Pixelon” on the left breast. There wasn’t much in the yurt, but Luca furtively gathered some books and papers before descending and alerting the authorities. His mediocre English kept him from deciphering what he’d found, and comprehending this man’s story fully, but he’d gleaned enough to decide that, because I teach poetry writing and live in San Francisco, I was—at least, in Luca’s mind—the obvious person to put on the case.

Luca’s package arrived a week later. Here is what I learned.

* * *

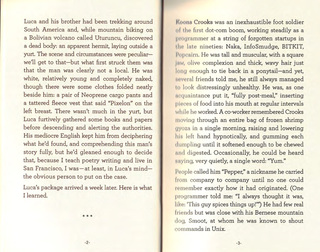

Koons Crooks was an inexhaustible foot soldier of the first dot-com boom, working steadily as a programmer at a string of forgotten startups in the late nineties: Naka, InfoSmudge, BITKIT, Popcairn. He was tall and muscular, with a square jaw, olive complexion and thick, wavy hair just long enough to tie back in a ponytail—and yet, several friends told me, he still always managed to look distressingly unhealthy. He was, as on acquaintance put it, “fully post-meal,” inserting pieces of food into his mouth at regular intervals while he worked. A worker remembered Crooks moving through an entire bag of frozen shrimp gyoza in a single morning, raising and lowering his left hand hypnotically, and gumming each dumpling until it softened enough to be chewed and digested. Occasionally, he could be heard saying, very quietly, a single word: “Yum.”

People called him “Pepper,” a nickname he carried from company to company until no one could remember exactly how it had originated. (One programmer told me: “I always thought it was, like: ‘This guy spices things up!'”) He had few real friends but was close with his Bernese mountain dog, Smoot, at whom he was known to shout commands in Unix.

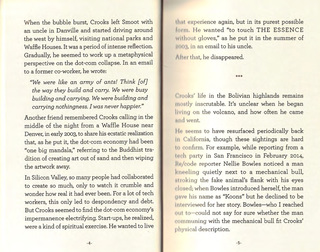

When the bubble burst, Crooks left Smoot with an uncle in Danville and started driving around the west by himself, visiting national parks and Waffle Houses. It was a period of intense reflection. Graduallly, he seemed to work up a metaphysical perspective on the dot-com collapse. In an email to a former co-worker, he wrote:

“We were like an army of ants! Think [of] the way they build and carry. We were busy building and carrying. We were building and carrying nothingness. I was never happier.”

Another friend remembered Crooks calling in the middle of the night from a Waffle House near Denver, in early 2003, to share his ecstatic realization that, as he put it, the dot-com economy had been “one big mandala,” referring to the Buddhist tradition of creating art out of sand and then wiping the artwork away.

In Silicon Valley, so many people had collaborated to create so much, only to watch it crumble and wonder how real it had ever been. For a lot of tech workers, this only led to despondency and debt. But Crooks seemed to find the dot-com economy’s impermanence electrifying. Start-ups, he realized, were a kind of spiritual exercise. He wanted to live that experience again, but in its purest possible form. He wanted “to touch T H E E S S E N C E without gloves” as he put it in the summer of 2003, in an email to his uncle.

After that, he disappeared.

* * *

Crooks’ life in the Bolivian highlands remains mostly inscrutable. It’s unclear when he began living on the volcano, and how often he came and went.

He seems to have resurfaced periodically back in California, though these sightings are hard to confirm. For example, while reporting from a tech party in San Francisco in Feburary 2014, Re/code reporter Nellie Bowles noticed a man kneeling quietly next to a mechanical bull, stroking the fake animal’s flank with his eyes closed; when Bowles introduced herself, the man gave his name as “Koons” but he declined to be interviewed for her story. Bowles—who I reached out to—could not say for sure whether the man communing with the mechanical bull fit Crooks’ physical description.

Meanwhile, the venture investor Chris Sacca recalls a man named Koons approaching him on a ski slope in Truckee in either 2011 or 2012, asking for a meeting. The man had no skis on, or even boots. When Sacca asked for his contact information, as a way to politely wiggle out of the confrontation, the man pulled a tattered business card out of his wallet, used a Sharpie to cross out the name and details of the Palo Alto-based podiatrist on it, then paper-clipped a small, dried wildflower to the blank side, put the card in Sacca’s hand, and wandered off into the snow.

Beyond food and camping gear, Crooks had very few personal items with him in the yurt: one change of clothes, a solar-powered laptop and satellite wi-fi hotspot that he seems to have built himself, an iPod shuffle with exactly one song (“Even Flow”), a photograph of Vannevar Bush and a small, utterly inexplicable selection of hardback books: four volumes about deep-sea exploration (including one by a former roommate, James Nestor) and a copy of Chez Panisse Vegetables.

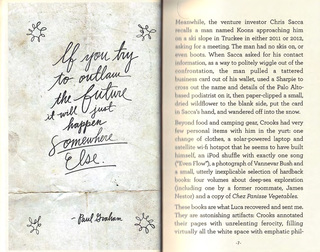

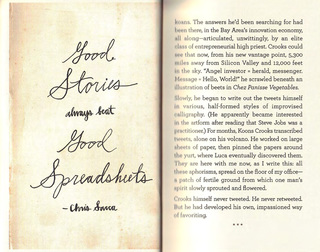

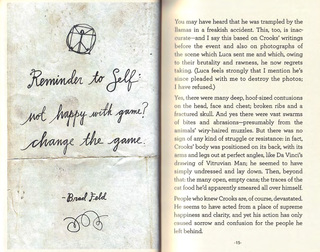

These books are what Luca recovered and sent me. They are astonishing artifacts: Crooks annotated their pages with unrelenting ferocity, filling virtually all the white space with emphatic philosophical treatises or disjointed bursts of observation; it was as though he were reading, and responding to, other books entirely. In fact, he had crossed out the titles on their covers and scrawled the same new one on each: “Iterating Grace.”

Other diary-like entries in the margins describe Crooks’ pared down, monastic lifestyle. He took walks. He foraged. He dried wildflowers and grasses. He collected interesting rocks, and numbered each one sequentially with a Sharpie. He devoted much of his time to contemplating ecology, which he called “the ultimate operating system.” And with increasing frequency, it seems, he checked Twitter.

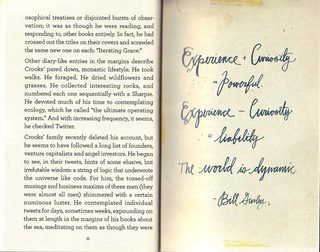

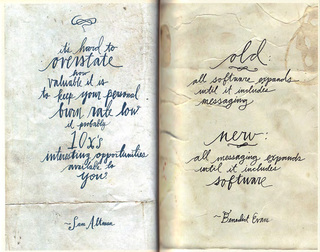

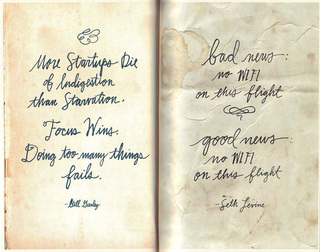

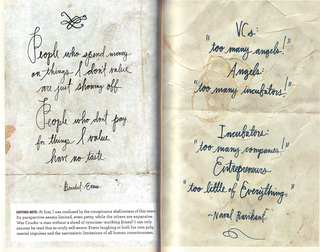

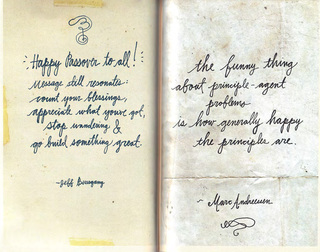

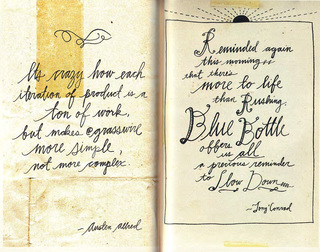

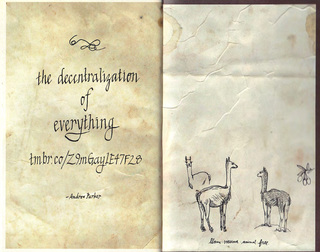

Crooks’ family recently deleted his account, but he seems to have followed a long list of founders, venture capitalists and angel investors. He began to see, in their tweets, hints of some elusive, but irrefutable wisdom: a string of logic that underwrote the universe like code. For him, the tossed-off musings and business maxims of these men (they were almost all men) shimmered with a certain numinous luster. He contemplated individual tweets for days, sometimes weeks, expounding on them at length in the margins of his books about the sea, meditating on them as though they were koans. The answers he’d been searching for had been there, in the Bay Area’s innovation economy, all along—articulated, unwittingly, by an elite class of entrepreneurial high priest. Crooks could see that now, from his new vantage point, 5,300 miles away from Silicon Valley and 12,000 feet in the sky. “Angel investor = herald, messenger. Message = Hello, World!” he scrawled beneath an illustration of beets in Chez Panisse Vegetables.

Slowly, he began to write out the tweets himself in various, half-formed styles of improvised calligraphy. (He apparently became interested in the artform after reading that Steve Jobs was a practitioner.) For months, Koons Crooks transcribed tweets, alone on his volcano. He worked on large sheets of paper, then pinned the papers around the yurt, where Luca eventually discovered them. They are here with me now, as I write this: all these aphorisms, spread on the floor of my office—a patch of fertile ground from which one man’s spirit slowly sprouted and flowered.

Crooks himself never tweeted. He never retweeted. But he had developed his own, impassioned way of favoriting.

* * *

Maybe you’ve heard the gossip around the Valley and think you know how this story ends. But, I discovered, there are a lot of misconceptions about the llamas.

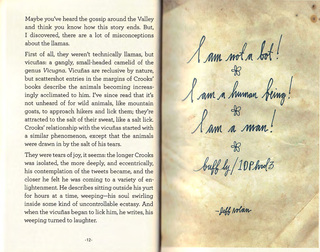

First of all, they weren’t technically llamas, but vicuñas: a gangly, small-headed camelid of the genus Vicugna. Vicuñas are reclusive by nature, but scattershot entries in the margins of Crooks’ books describe the animals becoming increasingly acclimated to him. I’ve since read that it’s not unheard of for wild animals, like mountain goats, to approach hikers and lick them; they’re attracted to the salt of their sweat, like a salt lick. Crooks’ relationship with the vicuñas started with a similar phenomenon, except that the animals were drawn in by the salt of his tears.

They were tears of joy, it seems: the longer Crooks was isolated, the more deeply, and eccentrically, his contemplation of the tweets became, and the closer he felt he was coming to a variety of enlightenment. He describes sitting outside his yurt for hours at a time, weeping—his soul swirling inside some kind of uncontrollable ecstasy. And when the vicuñas began to lick him, he writes, his weeping turned to laughter.

You may have heard that he was trampled by the llamas in a freakish accident. This, too, is inaccurate—and I say this based on Crooks’ writing before the event and also on photographs of the scene which Luca sent me and which, owing to their brutality and rawness, he now regrets taking. (Luca feels strongly that I mention he’s since pleaded with me to destroy the photos; I have refused.)

Yes, there were many deep, hoof-sized contusions on the head, face and chest; broken ribs and a fractured skull. And yes there were vast swarms of bites and abrasions—presumably from the animals’ wiry-haired muzzles. But there was no sign of any kind of struggle or resistance: in fact, Crooks’ body was positioned on its back, with its arms and legs out at perfect angles, like Da Vinci’s drawing of Vitruvian Man; he seemed to have simply undressed and lay down. Then, beyond that: the many open, empty cans; the traces of the cat food he’d apparently smeared all over himself.

People who knew Crooks are, of course, devastated. He seems to have acted from a place of supreme happiness and clarity, and yet his action has only caused sorrow and confusion for the people he left behind.

Happiness? Clarity? Are we sure this was his mindset? I think we can be. Because there is one other detail: a small, badge-like piece of paper, which Crooks had crudely laminated with plastic wrap, then tied around his neck with a lanyard, as though he’d just registered at his final conference. By the time Luca found him, vultures or other scavengers had taken one of Crooks’ eyes and most of an ear. Elsewhere, maggots were doing their work.

Luca reports that Crooks’ body had already started to decompose to such a degree that, in certain places, the boundary between it and the soil beneath it had blurred. Koons Crooks—“Pepper”—was becoming granular: converting into dust and earth and nutrients, just as he apparently intended. His broken mouth was still smiling, and on that little sign around his neck, he’d written:

THE SHARING ECONOMY ;)

Newsletter from Robin Sloan <robin@robinsloan.com>

10/06/15 18:13

‡ The strange case of Iterating Grace

GREETINGS, Society of the Double Dagger.

This message will be brief and unorthodox; I didn't have any plans to write at all, but something emerged this week that's so weird and cool and plainly up your alley that I feel basically required to share it.

Remember: you're getting this email because you signed up to hear from me, Robin Sloan, author of Mr. Penumbra's 24-Hour Bookstore and a few other things. I am now on the third draft of my new novel. Maybe fourth. Depends how you count. I'll send another message when it's finished, I promise!

So.

Here's the setup.

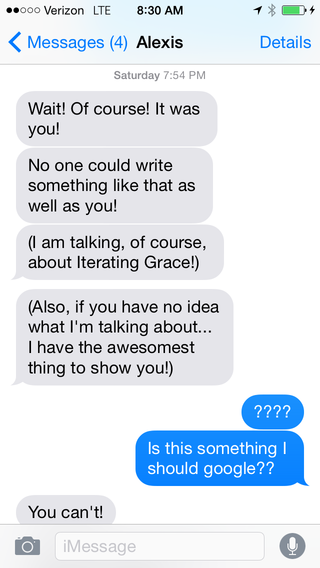

A friend of mine named Alexis Madrigal texted me the other night:

A few minutes later, he walked over carrying a very slim book that, he explained, had been delivered to his doorstep. The cover bore the title Iterating Grace. It listed no author. Alexis plopped down on my couch and began to read it aloud.

The story is scant: around 2000 words. The format beefs it up, makes it feel more substantial than it is. But here's the important thing: it's really good! It purports to be the author's recollection of a character named Koons Crooks. (Koons. Crooks.) It's a slow-burn satire set in the San Francisco tech world, dark but not too dark, enlivened by wonderful details. Oh, and there are calligraphic tweets:

According to the story, Crooks copied out the tweets -- all beautifully "profound" bloviations from venture capitalists -- while living as a hermit (with satellite internet) in the Bolivian highlands.

Yep.

On Monday, Alexis performed a public service by digitizing the entire book, calligraphy and all. He also laid out the clues, which are scant indeed.

Here's the truth: we have no idea who wrote this. More cynical minds assume it's a viral marketing scheme; that's certainly possible, but I doubt it, simply because the writing is too good. This story has the mark of authentic authorship. It has real spirit.

As you'll see in Alexis's post, there are good reasons to believe the mystery author resides here in the Bay Area and is part of our broad social network. My dream, though, is that the author is someone new; that this is his/her public debut. It would be astonishing!

I should add that many people -- like, really quite a few -- have accused me of being the mystery author, which is both a great compliment, because I think it's a wonderful piece of work, and a bit of a sting, because wow I wish it was me doing something this clever. In any case, I think careful reading exonerates me; I'm not the kind of writer to end a story with a scene so funny-bleak, so borderline Vonnegut. (I also hope I'm not the kind of writer to send a message to his entire email list pretending not to be the author of… you get it.)

But who might have written this? The suspects are legion and yet the lineup feels… off somehow. Paul Ford? Joshua Cohen? James Nestor? Wendy MacNaughton and Caroline Paul? James Freeman, the founder of Blue Bottle Coffee?? I explored the use of stylometric analysis (because of course I did) but the technique depends on a fairly large pool of candidate authors, and I can't say that I know of a single solid candidate. Not yet.

Maybe after you get through the story, you'll have a suspect of your own. I really do encourage you to give it a look; it's an eminently readable 2000 words, and come on! This is something straight out of the Penumbra-verse!

Nice to know this sort of thing really happens, isn't it?

Have a great summer,

Robin

P.S. While I'm here: recently, working with my friend Tim Hwang and the Data & Society Institute in New York City, I wrote a little sci-fi short story. It's called "The Counselor."

P.P.S. If this really is viral marketing I'm going to be so mad.

Robo-pirates should unsubscribe immediately.

JavaScript is turned off.

Please enable JavaScript to view this site properly.